Resurrection Preserved: Hilton’s Lazarus and St Mary’s Reawakening

By Barry Richardson

As with much of the Re‑Awakening, people have been given a once‑in‑a‑generation chance to see St Mary’s up close. This is an unexpected bonus with glimpses of corners long hidden from view.

On the north wall of St Mary Magdalene’s, Newark, above the North Porch, hangs a painting once central to the church: The Raising of Lazarus. A few weeks ago scaffolding stood beneath it. A ladder reached upward. Anna Herbert, Heritage Interpretation and Visitor Experience Manager, climbed — and this week’s blog began.

Pre-Re-Awakening - The Raising of Lazarus pictured, framed above the North Porch

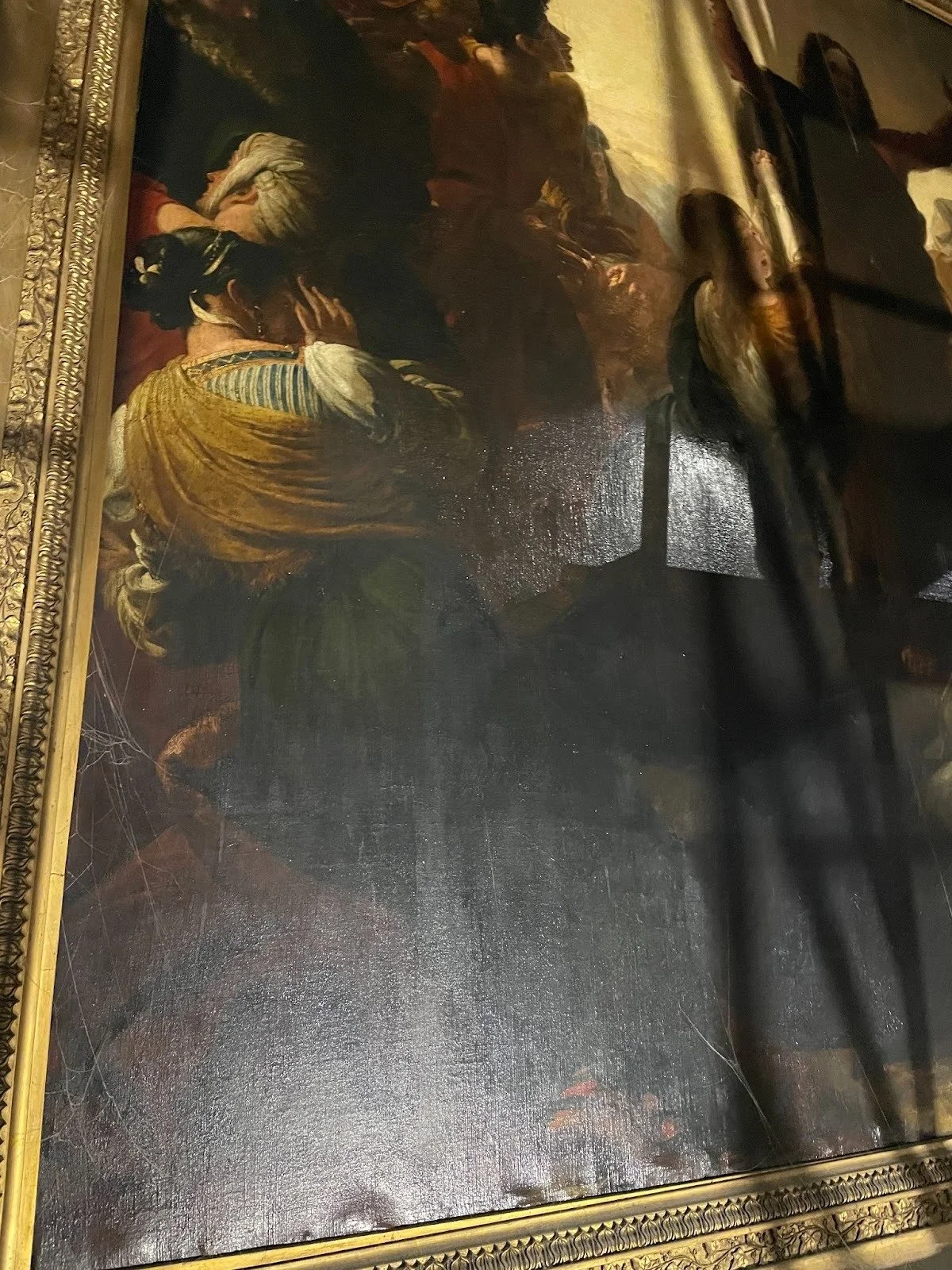

The view from closer up showing the incredible detail on this expansive painting(and cobwebs)

Mirroring Re-Awakening

The raising of Lazarus mirrors the re‑awakening of St Mary’s. The church was never dead — only weathered and waiting.

Yet the parallel is striking: renewal, restoration, return of life as a central hub for Newark’s community.

Quick Story Recap

Lazarus was brother to Mary and Martha of Bethany. Not Mary Magdalene — the patron saint of this church — but another Mary, another story. Four days in the tomb. Christ commands. Lazarus rises. Witnesses recoil in astonishment.

The awe of the command to rise from the dead and the onlookers astonishment and wonder is clearly visible

Hilton’s Gift

This vast canvas by William Hilton RA is more than art. It is Newark’s story — a gift from one of its own sons, faith and heritage intertwined.

Hilton, born in Lincoln in 1786 to a Newark painter, rose to national prominence in the early nineteenth century. Royal Academy Schools. Royal Academician in 1819. Keeper of the Academy. Grand biblical canvases. Portraits of Clare and Keats. Reputation secured.

The painting seen directly, muted by age but still exuding the power of resurrection

Looking Home

In 1821 Hilton turned homeward. He presented this monumental work to St Mary’s. For three decades it was the altarpiece. The congregation confronted resurrection.

Victorian zeal displaced it. A new reredos rose. Hilton’s canvas moved above the North Porch. Muted by age, yet still charged with resurrection’s power.

Close up reveals the astonishing colour and detail of the painting

Composition and Presence

Christ commands. Lazarus steps forth. Figures recoil. Theatrical energy. Astonishment captured in brush and colour. No longer the liturgical centre, yet still a voice across centuries. A reminder of Newark’s artistry. A gift enduring.

A copy of the painting, spotted hanging in a Leicestershire Church which gives a slightly clearer impression of the vibrancy and power of the original.

Final Thoughts

To stand before Hilton’s canvas is to encounter history: nineteenth‑century ambition, Victorian change, and the enduring resonance of Lazarus. In this single work, scripture’s drama, local artistry, and shifting ecclesiastical fashion converge — aligning with the Re‑Awakening, a bold re‑imagining of the church in facility, accessibility, and endeavour.

As St Mary’s reawakens — fabric restored, spaces reclaimed, story retold — the painting becomes more than heritage. It becomes a metaphor. Just as Lazarus rose at Christ’s call, St Mary’s prepares to rise again — renewed for today’s generation.

The Re‑Awakening is, in every sense, its own resurrection: splendour awaiting, renewal prepared, vision ready to unfold. And that moment is near — weeks away, within reach, almost upon us.